In the beginning of April 2014, at a conference initiated by the Indian government, Manmohan Singh casually urged the creation of a global convention to forswear the first use of nuclear weapons. Why the Indian prime minister chose to make this major policy declaration in the last hours of his term in office is a mystery.

To unravel this mystery, it is important to note the context. Singh was addressing a conference at the Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses (IDSA) titled “A Nuclear Weapon-Free World: From Conception to Reality.” The IDSA is supported by the Indian Ministry of Defense and has been a favored venue for India’s leadership to make important policy declarations on national security. The Indian bureaucracies that deal with foreign policy and security issues often use this forum to articulate their preferences on arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament issues. It would be natural if these bureaucracies wished to commend the virtues of continuity in policy to the new Indian government headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who took office in May 2014.

Following Singh’s remarks, the then opposition Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) instantly issued a rejoinder in its election manifesto, stating that the party “believes that the strategic gains acquired by India during the [earlier BJP-led] Atal Behari Vajpayee regime on the nuclear programme have been frittered away by [Singh’s] Congress.” Hence, the BJP pledged to “study in detail India’s nuclear doctrine, and revise and update it, to make it relevant to [the] challenges of current times.”

BJP spokespeople clarified that a review of India’s no-first-use policy would be accorded priority if the party came to power. This evoked great concern in some quarters that the BJP would abandon no first use, which has been a central feature of India’s nuclear doctrine since the country conducted a series of nuclear tests in 1998 and established itself as a nuclear weapons state. The BJP’s Modi, campaigning for the 2014 election, subsequently declared that there would be “no compromise” on no first use, which reflected India’s “cultural inheritance” (whatever that means). But as the respected Economic and Political Weekly commented in an editorial: “Given the BJP’s naturally aggressive posture, such clarifications must be viewed with some scepticism and it is legitimate to explore what may be on the agenda.”

All this rhetoric is par for the course in the heated atmosphere of the Indian electoral process. Disconcertingly, both the Congress party and the BJP have forgotten the historical record. India’s no-first-use policy was originally declared by the BJP and the National Democratic Alliance government after it conducted the May 1998 nuclear tests. The prime minister at the time, Atal Behari Vajpayee, stated thereafter that India would pursue a policy of no first use of nuclear weapons vis-à-vis other nuclear-armed states and would not use these weapons against nonnuclear countries. This restraint was also embedded in the BJP’s draft nuclear doctrine , declared in August 1999, which took several years to be finalized. It was finally endorsed by the Cabinet Committee on Security and officially promulgated in January 2003.

Consequently, India’s no-first-use policy and its nuclear doctrine are BJP formulations. The Congress party adopted them and, with Singh’s April speech, simply sought to extend no first use globally. This makes the BJP’s concern with its own no-first-use policy and nuclear doctrine part of the mystery of Singh’s proposal.

The Limitations of Nuclear Deterrence

There are valid grounds to revisit India’s nuclear doctrine, as much has happened over the intervening years that challenges the assumptions made by the BJP. On the conceptual front, the limitations of nuclear deterrence have become apparent. In important ways, India’s acquisition of nuclear weapons has not increased its security.

While nuclear weapons have obvious relevance for the external dimensions of national security, they cannot ameliorate threats to India’s territorial integrity that arise from domestic discontent or from crossborder militancy and terrorism emanating from Pakistan. In other words, nuclear weapons cannot provide any defense against the subconventional threats to India’s national security from extremist elements within its own territory or, especially, against those who receive moral and material assistance from across the border. As Singh repeatedly warned, the internal threats to India’s national security are critical to its overall national security challenges. Nuclear weapons provide no defense against these dangers.

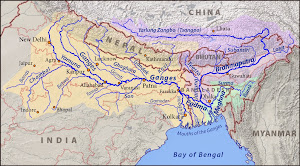

The evidence in this regard is overwhelming and discernible from continuing unrest in the state of Jammu and Kashmir and in northeast India and from Maoist violence in central and east India. Further, after Pakistan followed suit with its own nuclear tests in 1998, India’s superiority in conventional forces was conspicuously eroded. This can be seen in India’s fitful responses to incidents of crossborder terrorism from Pakistan and its thus far confused approach to the concept of Cold Start and delay in establishing the forces required to operationalize it. [1]

Nuclear deterrence can only provide security against the use of nuclear weapons or a major conventional attack. This ineluctable reality evades India’s strategic elites and its armed forces establishment. They find it hard to accept that nuclear weapons, unlike other weapon systems, are not designed for use and cannot achieve strategic objectives like gaining territory or dominating populations. Moreover, these weapons’ immense destructive potential within very short time frames and their ability to cause genetic mutations over generations ensure that they are essentially meant to deter their use by an adversary. In other words, nuclear deterrence cannot accomplish any vital national security goals other than preventing an adversary from using nuclear weapons.

In a larger sense, no doubt, nuclear deterrence permits peaceful conditions to be established, a situation that is conducive to economic progress and the stimulation of regional trade and commerce. However, an entire spectrum of security threats also arises, ranging from border incursions to subconventional warfare and crossborder terrorism and militancy. Nuclear weapons provide no security against this range of existential security threats.

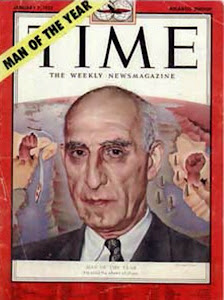

These fuller implications of the nuclear tests were not thought through before the tests were conducted in 1998. Perhaps these limitations surrounding nuclear deterrence were not knowable in advance. But this belief is questionable. It was known, for instance, that India would be subjected to punitive economic and technological sanctions that would affect its growth and poverty alleviation programs in response to the nuclear tests. Indeed, India’s earlier experience after its so-called “peaceful nuclear explosion” in May 1974 was a forewarning that further nuclear tests would not enable India’s entry into the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as a nuclear weapons state and that the imposition of more stringent sanctions was certain.

According to available evidence, the decision to conduct the nuclear tests in May 1998 was made by a very small coterie around Vajpayee. He and his advisers believed that India needed to go nuclear to meet the nuclear threats from Pakistan and China, elevate India in the comity of nations, and fulfill the pledge in the BJP’s 1996 election manifesto to conduct nuclear tests if the party came to power. The rest is history: sanctions on India’s civilian nuclear program were reinforced, severely impeding its progress—despite tall claims that the restrictions provided a fillip to indigenous research and development.

India’s Atomic Energy Commission has traditionally argued that sanctions on importing nuclear technology, equipment, and materials from abroad did not hurt, since the commission could harness the human and technical resources available in the country to meet its requirements. This bravado was first expressed after India conducted its 1974 nuclear test. It is clear, however, that despite some limited success, India remained dependent on foreign assistance to establish its nuclear infrastructure. This fact was reflected in the United Progressive Alliance government’s rationale for entering into the Indo-U.S. nuclear deal in 2008, namely to rescue India from its “ nuclear pariah” status and open the way for imports of nuclear materials and technology.

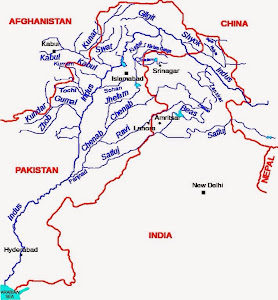

The establishment of nuclear deterrence vis-à-vis Pakistan had only limited value for India’s overall national security. It did not deter Pakistan’s crossborder incursions in winter 1998 and spring 1999 into the Kargil sector of Jammu and Kashmir, which led to a short but intense conflict ending in the ouster of Pakistan’s regular and irregular forces. Pakistan had the advantage of surprise, but its intruders were no match for India’s superior conventional forces, which were brought into the Kargil and neighboring sectors of the Line of Control. Yet despite India’s overwhelming superiority in conventional arms, the effects of nuclear deterrence inhibited it from attacking Pakistan’s lines of communications across the border or from enlarging the theater of conflict along the border to relieve pressure on the beleaguered Kargil sector. Pakistan was disadvantaged by its need to maintain the fiction that militants had conducted these intrusions, and therefore it could not openly deploy its regular forces to defend them. Significantly, these operations revealed that a nuclearized Pakistan had constrained New Delhi from launching a counteroffensive elsewhere along the Line of Control or into Pakistan to relieve pressure on Indian forces in Kargil. New Delhi decided that it would exhibit restraint and not expand the theater of conflict. Political considerations were said to be at play, as India wished to establish that it was a responsible nuclear power by not escalating the conflict.

There was also a subliminal desire among Indian leaders to paint Pakistan into a corner by highlighting its irresponsible conduct in attacking across recognized borders without any provocation. In pursuance of this policy of restraint, the Indian Air Force was given strict orders not to attack Pakistani territory across the Line of Control or enter Pakistan’s airspace. The ground forces were similarly prohibited from expanding the area of conflict along the Line of Control to relieve pressure on the Kargil sector. There is little doubt, however, that this restraint was also informed by New Delhi’s awareness that an escalation of this border conflict could become uncontrollable and lead inexorably toward the nuclear threshold.

Pakistan Ups the Ante

A similar sequence of events inhibited India during its border confrontation crisis with Pakistan after an attack by Pakistan-based militants on the Indian parliament in mid-December 2001. India moved large elements of its armed forces to the India-Pakistan border, where they remained for almost one year. Unable to mount an attack into Pakistan, they returned without achieving anything worthwhile. Again, in November 2008, New Delhi found itself constrained in retaliating against brazen attacks by Pakistan-sponsored militants on several high-profile targets in Mumbai.

More generally, it would seem that Pakistan has acquired virtual impunity in launching terrorist attacks at will into India through organizations that enjoy its patronage, like Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jamaat-ud-Dawa. Admittedly, these groups operate in collaboration with local militants like the Indian Mujahideen, but leadership, funding, training, and sanctuary are provided by Pakistan. Despite grave provocation by these groups, India has been unable to undertake any punitive counterstrike but has sought redress by painting Pakistan into an ideological corner within the international system.

A more general argument against nuclear deterrence was made by the four horsemen, George Shultz, Henry Kissinger, Sam Nunn, and William Perry, in 2007 in theWall Street Journal. “Nuclear weapons were essential to maintaining international security during the Cold War because they were a means of deterrence. The end of the Cold War made the doctrine . . . obsolete. Deterrence continues to be a relevant consideration for many states. . . . But reliance on nuclear weapons for this purpose is becoming increasingly hazardous and decreasingly effective.”

Pakistan’s decision to deploy tactical nuclear weapons in a battlefield mode along the India-Pakistan border can be surmised from a report by Hans M. Kristensen and Robert Norris of the Federation of American Scientists that identified Pakistan and China as either having or developing nonstrategic nuclear weapons. Pakistan had made clear, Kristensen told the Times of India , that it was developing its nuclear-capable Nasr (or Hatf IX) missile “for use against invading Indian troop formations that Pakistan doesn’t have the conventional capabilities to defeat.” These weapons, according to Indian experts, are meant to be used along the border in case of any skirmish with the Indian Army. The Nasr is described as “a 60-kilometer [37-mile] ballistic missile launched from a mobile twin-canister launcher.” According to Pakistan’s Inter Services Public Relations, the Nasr also has “shoot and scoot attributes” to serve as a quick response system to “add deterrence value” to Pakistan’s strategic weapons development program “at shorter ranges . . . to deter evolving threats.”

These developments have highlighted the insufficiency of India’s no-first-use policy to deter Pakistan’s destabilizing strategy. For one thing, this policy articulation frees Pakistan of the uncertainty and angst that India might contemplate the preemptive use of nuclear weapons to deal with terrorist attacks or limited conventional strikes by Pakistan. Pakistan could also go to the extent of deploying its short-range Nasr missile without being concerned that India would target it with its own nuclear missiles. For another, the determinism inherent in India’s nuclear doctrine that any level of nuclear attack will invite massive retaliation is too extreme to gain much credibility. It defies logic to threaten an adversary with nuclear annihilation to deter or defend against a tactical nuclear strike on an advancing military formation.

Moreover, in an adversarial situation between two nuclear powers, recourse to massive retaliation by one side would surely trigger a similar counterattack. How would the mutual annihilation that would undoubtedly ensue serve the ends of national security? This is a question that must induce greater reflection on how to devise a more appropriate strategy to meet Pakistan’s threat of using tactical nuclear weapons in crises along the India-Pakistan border.

Pakistan, for its part, has not countenanced a no-first-use policy on the grounds that the weaker conventionally armed power has to rely on nuclear weapons to ensure its security. However, conventional wisdom warns that deployment of nuclear weapons along the border makes these arms vulnerable to attack, which, in turn, could generate a “use or lose” mentality on the part of their possessor. A related danger that has not been sufficiently articulated is that nuclear missiles situated near the border could become vulnerable to targeting by long-range artillery, apart from special forces operations, highlighting the hair-trigger nature of such deployments. Pakistan argues that locating tactical nuclear weapons along the India-Pakistan border in a state of battle-readiness enables it to counter India’s Cold Start strategy, which envisages positioning offensive, battle-ready forces along the India-Pakistan border to deter any crossborder attack.

In this fashion, according to one nuclear expert, “Pakistan has upped the nuclear ante in South Asia by choosing to adopt tactical nuclear weapons . . . because they lower the nuclear threshold, the point at which nuclear weapons are brought into use. As such, they are straining South Asia’s deterrence stability, the idea that roughly equivalent nuclear capabilities will deter adversaries from using these weapons.” Pakistan claims that deploying its tactical nuclear weapons would provide it with “full spectrum deterrence” against India. Rawalpindi would also be enabled to counter any offensive operations India might contemplate against Pakistan in response to another Mumbai-style terrorist attack.

The particular danger of this deployment pattern is that it creates pressures to delegate to field commanders the authority to use these missiles in a crisis situation. Pakistani authorities insist that no such delegation would be necessary. In the end, and especially with the fog of war intervening, whatever arrangements were thought to control such weapons could never be foolproof. The possibility of human error would have to be accepted. But, with nuclear weapons entering the calculus, such errors could have horrific consequences.

Adding to these uncertainties is the fact that the internal situation in Pakistan has been rapidly deteriorating over the last few years, with extremist and religious fundamentalist groups exercising control over growing areas in the country. Political differences between the military and civilian leaderships in Pakistan are also increasing, with the judiciary functioning not as an umpire but as a third leg in an unstable relationship between elements of the country’s ruling elite. How this increasingly dysfunctional system can implement a responsible nuclear strategy is an open question.

An impasse has now been reached that threatens the stability of India-Pakistan relations. It is arguable that India’s commitment to a no-first-use posture has encouraged Pakistan to adopt its present adventurist strategy, secure in the belief that it could undertake provocative actions without the angst that India might contemplate a nuclear riposte. Its provocative actions would include promoting crossborder militancy and terrorism into India and even brazen actions like the attack on the Indian parliament in 2001 or the Mumbai attacks in 2008. Arguably, the adoption of a deliberately vague policy in regard to nuclear retaliation by India, instead of the certitude of a no-first-use declaration, might have better served India’s overall strategic ends.

Apart from that, the no-first-use policy, which has been incorporated into India’s nuclear doctrine, has several other infirmities.

An Inadequate Doctrine

The decision by the Cabinet Committee on Security to endorse India’s nuclear doctrine makes clear that India will use nuclear weapons only to retaliate against a nuclear attack on its territories or on Indian forces anywhere; that nuclear weapons will not be used against nonnuclear states; but that, in the event of a major attack by biological or chemical weapons, India retains the option of retaliating with nuclear weapons. This enumeration of India’s qualified no-first-use policy doctrine is flawed on several counts.

First, it does not address the possibility of an attack by nonstate actors, which is the present and imminent danger. Would the country hosting those nonstate actors be targeted following such an attack? And how would India address an attack by an international organization like al-Qaeda that is situated in several countries in the proximity of India?

Second, how would a “major attack” with biological or chemical weapons be identified? What is “major” and what is “minor” is debatable. This issue is significant since biological and chemical weapons are not truly weapons of mass destruction, but they are certainly weapons of mass disruption. Nonstate actors might favor these weapons due to the comparative ease of their manufacture, concealment, and transportation.

Third, serious difficulties arise in any attempt to identify the perpetrator of a biological or chemical weapons attack that could be undertaken by state or nonstate actors or, not inconceivably, by a nonstate actor assisted by a state actor. This issue is ultimately a question of reliable forensics, which is at a rudimentary stage of development. The difficulty in identifying those guilty of chemical weapon attacks in Syria is instructive here.

India’s no-first-use declaration cannot be separated from the country’s overall nuclear doctrine as it has been articulated since 1999. Inadequate as it is, this doctrine deserves to be reviewed in the light of changes over the past fifteen years.

The current nuclear doctrine dictates that nuclear retaliation against a first strike would be “massive” and designed to inflict “unacceptable damage” upon the attacker. This is an unrealistic certitude because, ethically, punishing large numbers of noncombatants contravenes the laws of war. Besides, threatening massive retaliation against any level of nuclear attack, which would inevitably trigger assured nuclear annihilation in a binary adversarial situation, is hardly a credible option. No doubt, it raises a ticklish question: Would India then favor a counterforce or countercity strategy? India’s stated adherence to an assured and massive second strike suggests the latter.

However, in addition to the other infirmities of a massive retaliation response, the uncomfortable reality is that the trade winds in May–September associated with the southwest monsoon blow from Pakistan into northern India. Consequently, secondary and tertiary radiation from a nuclear attack launched by India against Pakistan in these months would blow back into India’s agriculturally rich Punjab and Haryana states and, indeed, into New Delhi. India therefore faces a huge time constraint to mount a massive nuclear attack into Pakistan. Operationally, too, destroying the territory in dispute is feckless.

In a nuclear adversarial situation, moreover, the inevitability of mutual destruction must also be considered. Is a counterforce attack on the adversary’s military formations and assets the answer? The issue of uncontrollable escalation then arises, for which there is no reassuring answer. Leaving the problem of how India should retaliate to a nuclear first strike to the discretion of the prime minister would provide greater flexibility to mount the counterattack instead of threatening assured nuclear annihilation, which is just not credible.

India’s present chain of command with respect to nuclear weapons functions under the rubric of a Nuclear Command Authority and a Strategic Forces Command. The prime minister has been designated as the “release authority.” He has the unequivocal authority to decide whether, when, and how to use nuclear weapons. A Political Council headed by the prime minister constitutes the apex of this command structure. An Executive Council headed by the national security adviser serves the Political Council. Its composition includes the service chiefs and relevant government secretaries, including the scientific adviser to the prime minister.

The Strategic Forces Command is headed by a commander-in-chief; the incumbent comes from one of the three services of the Indian Armed Forces, on a rotating basis. The Strategic Forces Command is located within the Integrated Defense Headquarters in the Ministry of Defense. But it also functions under the Chiefs of Staff Committee. Its chairman is the most senior service chief, which ensures that the post rotates among the three services, without any fixed tenure. A conscious effort is evident, however, to assert the primacy of civilian control over the military at all levels of the nuclear command structure.

The element of doubt arising in this arrangement is that a tri-service command like the Strategic Forces Command should, logically, function under a single line of authority representing the three services, like a chief of defense staff, who would be a single-point adviser to the government on sensitive security issues. The proposal to establish a chief of defense staff, incidentally, is of ancient vintage and can be traced back to the Sino-Indian border conflict of 1962. The option of a chief of defense staff has been recommended by numerous inquiry committees, notably theArun Singh Committee on defense expenditure (in 1990) and, most recently, theNaresh Chandra Committee on national security. [2]

But this proposal to appoint a chief of defense staff who could provide a unified service view to the government on sensitive issues continues to languish since it has been resolutely opposed by the Indian Navy and Air Force. The attitude of the Ministry of Defense and the Government of India, which could force through a decision, can at best be described as studied insouciance. It remains unclear in these circumstances whether, in a crisis situation, the strategic forces commander would report to the chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee, which would be an unsatisfactory arrangement as far as civilian control is concerned, or whether he would report directly to the national security adviser and the Executive Council, which is equally unsatisfactory from an interservice coordination perspective.

It is for these reasons that it makes more sense for the decision about whether, when, and how to retaliate against a nuclear attack to remain the prime minister’s. Moreover, time would clearly be at a premium in a crisis situation. A committee system of decisionmaking is hardly suited to handle a fast-developing situation. Providing the “release authority” the greatest flexibility to decide how to mount the counterattack, according to the exigencies of the situation, provides a more workable solution to this problem.

The present doctrine fetishizes acquisition of a “credible minimum deterrent.” But India is seeking a force structure that is no different from that established by the United States or the former Soviet Union. India seeks a strategic triad comprising land-based, airborne, and underwater nuclear weapon systems that will require increasing resources.

It is arguable whether India’s strategic circumstances require a naval component for its deterrent or whether the country requires only a submarine-based deterrent, on the assumption that the nuclear deterrent posture ultimately rests on the survivability of the nuclear arsenal. Land- and air-based systems are more vulnerable to counterattack and destruction than submarine-based missiles are. That leads to the argument that taking the deterrent out to sea would ensure the acquisition of an invulnerable second strike capability. This question has not been seriously discussed in India, resulting in vociferous demands from the three services that the government concede some component of the nuclear deterrent to each of them.

Criticism is widespread that there is little transparency about the size and structure of India’s nuclear forces and what its credible minimum deterrent comprises in terms of weapons systems. Instead of debating this issue, official spokesmen have argued that it is impossible to define what a credible minimum deterrent requires since there can be no “fixity” in this regard, which suggests that the contours of the credible minimum deterrent are a moving target. Incidentally, India’s armed forces have been kept out of the nuclear decisionmaking process; hence, there is a touch of unreality about these declarations on nuclear force structures.

The survival of the chain of command also needs to be credibly ensured and made more transparent to provide leadership continuity in all eventualities. To achieve this objective, the Strategic Forces Command should be enjoined to maintain survivable, dispersed, and sheltered communications with multiple redundancies. Appropriate measures must be taken to ensure the safety and security of the nuclear stockpile at all times.

Conclusion

It should be emphasized that neither former Indian prime minister Manmohan Singh’s last-ditch attempt to universalize India’s qualified no-first-use policy nor the confusions created by BJP protagonists regarding their commitment to this policy are to be commended. A detailed study of India’s nuclear doctrine is required to address all the relevant issues in their totality.

Clearly, none of the underlying issues that bedevil the nuclear doctrine allows for easy answers. For instance, the question of whether the retaliatory nuclear counterattack should pursue a counterforce or countercity strategy can be argued interminably.

However, a reasoned debate on this and other controversial issues is overdue. India’s nuclear doctrine is not cast in tablets of stone. Circumstances change, making periodical reviews of the nuclear doctrine essential. India’s nuclear doctrine has not been revisited for over a decade. The issues that suggest themselves for review are India’s command-and-control arrangements, which require greater clarity; the threat held out of assured massive retaliation, which forebodes self-annihilation; imparting greater content to the objective of credible minimum deterrence; and revisiting or abandoning the no-first-use policy in light of its numerous deficiencies.

It would also be realistic to appreciate that India’s major nuclear security problems arise not from the postulates of its nuclear doctrine but from the complexities of its geostrategic situation. India confronts two nuclear adversaries—Pakistan and China—that enjoy close relations with each other. It is clear that Pakistan’s nuclear weapons are unequivocally directed against India and are under the command and control of the Pakistan Army. But the negotiation of nuclear issues and confidence-building measures has been left to Pakistan’s civilian bureaucracy, which clearly lacks authority and functions under the close supervision of the army. How, then, should India negotiate?

There is a global consensus that the real danger from Pakistan’s nuclear weapons emanates from militants gaining control over them. The impunity with which militants have attacked military installations and headquarters in Pakistan reveals the inability of the country’s armed forces to defend themselves, as well as the likely existence of insider collusion with nonstate actors. Still, the Pakistani establishment chooses to externalize its difficulties by undertaking dangerous maneuvers like developing its short-range Nasr missile for a tactical role, which is universally condemned as highly destabilizing.

The recent debate in India on reviewing the country’s no-first-use policy and its nuclear doctrine might only signify preelection rhetoric. But the essential problem that remains and will tax the government of Narendra Modi is how India plans to credibly engage Pakistan in the interests of nuclear stability in South Asia. More