Give credit to Vladimir Putin and his New York Times op-ed on Syria for sparking a new tactic for foreign leaders hoping to influence American public opinion. In recent weeks, Saudi Arabian political elites have followed Putin’s lead, using American outlets to express their distaste with the West’s foreign policy, particularly with regard to Syria and Iran.

In comments to the Wall Street Journal, prominent Saudi Prince Turki al-Faisal decried the United States for cutting a preliminary deal with Iran on its nuclear program without giving the Saudis a seat at the table, and for Washington’s unwillingness to oppose Assad in the wake of the atrocities he’s committed. Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to Britain followed with an op-ed in the New York Times entitled “Saudi Arabia Will Go It Alone.” The Saudis are clearly upholding the vow made by intelligence chief Bandar bin Sultan back in October to undergo a “major shift” away from the United States.

In light of the recent actions of the Obama administration, many allies are also frustrated and confused, and even hedging their bets in reaction to the United States’ increasingly unpredictable foreign policy. But of all the disappointed countries, none is more so than Saudi Arabia — and with good reason. That’s because the two countries have shared interests historically — but not core values — and those interests have recently diverged.

First, America’s track record in the Middle East in recent years has sowed distrust. The relationship began to deteriorate with the United States’ initial response to the Arab Spring, where its perceived pro-democratic stance stood at odds with the Saudi ruling elite. After Washington stood behind the elections that installed a Muslim Brotherhood government in Egypt and then spoke out against the Egyptian army’s attempt to remove President Mohammad Morsi, the Saudi royals were left to wonder where Washington would stand if similar unrest broke out on their soil.

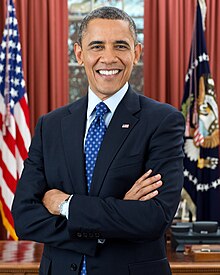

|

| Ian Bremmer |

Second, while the oil trade has historically aligned U.S.-Saudi interests, the unconventional energy breakthrough in North America is calling this into question. The United States and Canada are utilizing hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling techniques, leading to a surge in domestic energy production. That development leaves America significantly less dependent on oil from the Middle East, and contributes to the U.S.’ shifting interests and increasing disengagement in the region. Not only does Saudi Arabia lose influence in Washington — many of the top American executives in the oil industry were their best conduits — but it also puts the Saudis on the wrong end of this long-term trend toward increasing global energy supply.

To say that oil is an integral part of Saudi Arabia’s economy is a gross understatement. Oil still accounts for 45 percent of Saudi GDP, 80 percent of budget revenue, and 90 percent of exports. In the months ahead, new oil supply is expected to outstrip new demand, largely on the back of improvements in output in Iraq and Libya. By the end of the first quarter of 2014, Saudi Arabia will likely have to reduce production to keep prices stable. And the trend toward more supply doesn’t take into account the potential for a comprehensive Iranian nuclear deal that would begin to ease sanctions and allow more Iranian crude to reach global markets.

It is this ongoing nuclear negotiation with Iran that poses the principal threat to an aligned United States and Saudi Arabia. An Iranian deal would undercut Saudi Arabia’s leadership over fellow Gulf States, as other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members like Kuwait and the UAE would welcome resurgent trade with Iran. At the same time, Iran would emerge over the longer term as the chief competitor for influence across the broader region, serving as the nexus of Shi’ite power. The Saudis would find themselves most directly threatened by this Shi’ite resurgence within neighboring Bahrain, a majority Shi’ite state ruled by a Sunni regime that is backstopped by the Saudi royals.

The bottom line: the Saudis are actively competing with Iran for influence throughout the Middle East. That’s why the Saudis have the most at stake from any easing of sanctions on Iran, any normalization of relations with the West, or any nuclear breakthrough that gives Iran the ultimate security bargaining chip. The Saudis have reaped the benefits of an economically weak Iran — and they are not prepared to relinquish that advantage. Ultimately, any deal that exchanges Iranian economic security for delays in Iran’s nuclear program is a fundamental problem for Saudi Arabia — as is any failed deal that allows sanctions to unravel.

For all of these reasons, even though the United States will be buying Saudi oil for years to come and will still sell the Saudis weapons, American policy in the Middle East has now made the United States more hostile to Saudi interests than any other major country outside the region. That’s why the Saudis have been so vocal about the United States’ perceived policy failures.

But to say Obama has messed up the Middle East is a serious overstatement. What he has tried to do is avoid getting too involved in a messed up Middle East. Obama ended the war in Iraq. In Libya, he did everything possible to remain on the sidelines, not engaging until the GCC and Arab League beseeched him to — and even then, only in a role of “leading from behind” the French and the British.

Call the Obama policy “engaging to disengage.” In Syria, Obama did everything possible to stay out despite the damage to his international credibility. When the prospect for a chemical weapons agreement arose, he leapt at the chance to point to a tangible achievement that could justify the U.S. remaining a spectator to the broader civil war. In Iran, a key goal of Obama’s diplomatic engagement will be to avoid the use of military force down the road. It hasn’t always been pretty, but Obama has at least been trying to act in the best interests of the United States — interests that are diverging from Saudi Arabia’s. More